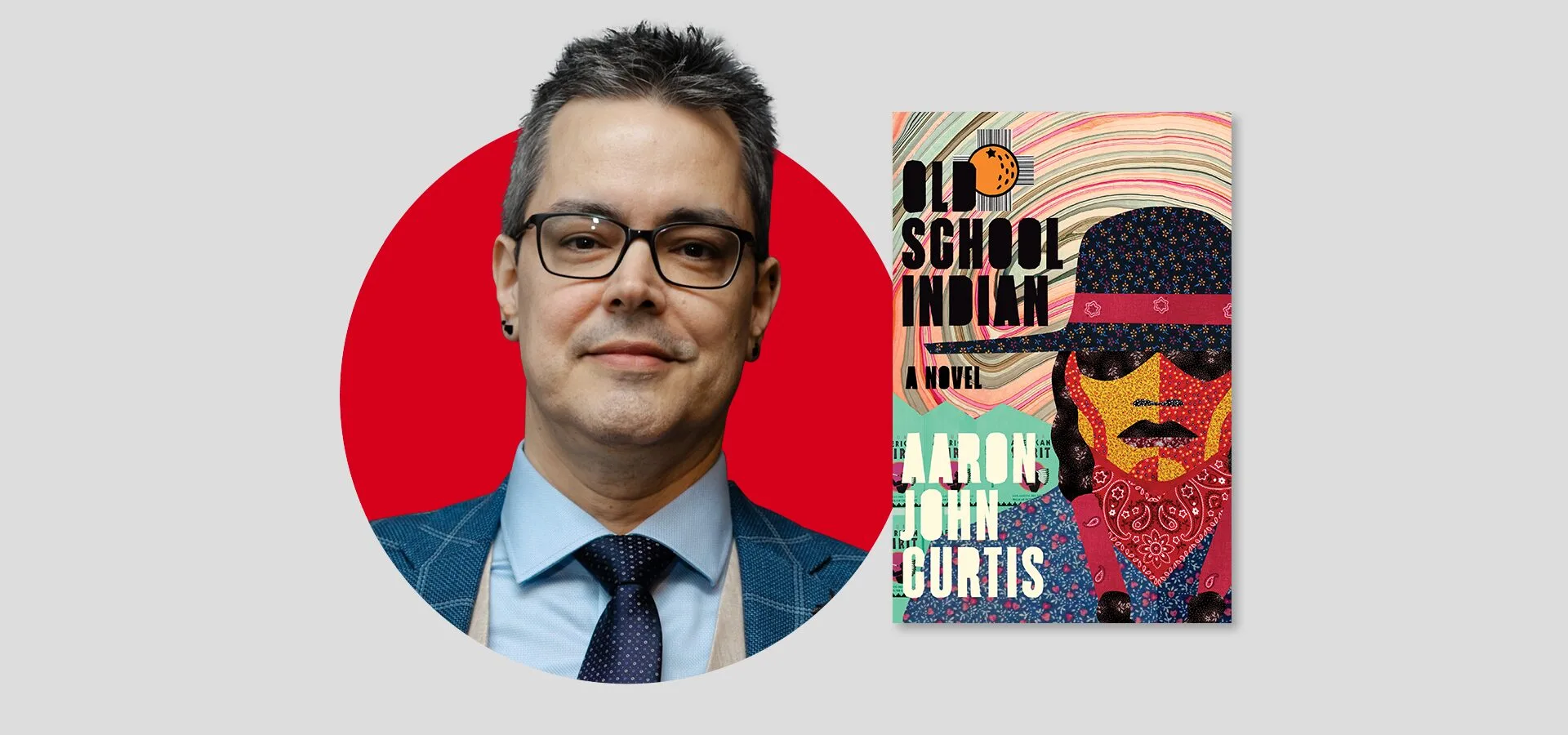

OLD SCHOOL INDIAN

Why The Windows Have To Be Open When Writing Poetry

Aaron John Curtis | The PEN Ten

The restorative and revelatory journey in Old School Indian, the debut novel by Aaron John Curtis, explores the impact that culture, community, and history have on an individual. Two decades after leaving the reservation where he was raised, Abe Jacobs, now a part-time poet in Miami whose marriage is about to collapse, is diagnosed with a rare disease that doctors believe will kill him. Returning to the Rez, where he grew up, Abe agrees to undergo traditional healing by his Great Uncle Budge despite his skepticism, and finds a new path forward with writing, healing, his family, and his relationship. (Zando – Hillman Grad Books, 2025)

In conversation with Digital Safety & Free Expression Program Coordinator Amanda Wells for this week’s PEN Ten, Curtis explains the importance of oral histories when researching, why illness is an impetus for change, and which significant aspect of Kanien’kehá:ka identity didn’t make it into the novel. (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble)

The “you” or, the audience, is very present in this novel. What reader did you have in mind as you were writing, and how did that guide the choices you made about what aspects of Abe and his culture to explain, and what to leave up for interpretation?

I normally write to entertain myself. Later, I trust my writers groups to tell me what’s working and what’s not. There are Easter eggs specifically aimed at Akwesasne Mohawk readers, but I assumed a mostly non-Native audience. I didn’t want to push anyone away, so I explained as much as I could. If there are gaps, then they’re either where I wanted to protect my family’s privacy, or they’re where my knowledge ran out.

Something that comes up often throughout this book is a sense of frustration and futility at trying to translate Native words into English–like the scene where Abe’s teacher tries to correct his translation of the word “Ionterahkwawehrhohstáhkhwa” as “umbrella.” Do you ever feel similarly about trying to capture Native experiences, traditions, and sentiments in your writing?

Writing about how Abe’s Tóta gave him an Indian name, which happens to be how I got my Indian name, I felt very conscious of the white gaze. Even though it was an authentic experience in my life, it felt like a performance of Indigenousness. So I wrote that into the book, how being Mohawk in America can sometimes feel like I’m wearing a costume. I had to include that so I could be authentic to my experience and my family’s experiences without feeling like I was playing into stereotypes.

What was it like to do research for this novel? Did you learn anything unexpected in the process?

Most of the research was keeping my ears open around family. I’ve amassed plenty of reading over the years to stay connected to the Rez while living in Miami –small press, self-published, or university press titles Haudenosaunee leaders and activists have written – and I’ve re-read some of them so many times I think the sociology and history just sticks. I used my nephew’s textbooks from when he took language classes for the Kanien’kéha (Mohawk language) I use. My mother gifted them to me. She’d been trying to remember the language which white schools had taken from her but it wasn’t working, so she handed them to me and said, “I hope you can do something with these.” I knew Tóta, the word for grandparent, was gender irrelevant but I was surprised the words for mother and aunt were the same, the words for father and uncle, for husband and wife.

So I wrote that into the book, how being Mohawk in America can sometimes feel like I’m wearing a costume. I had to include that so I could be authentic to my experience and my family’s experiences without feeling like I was playing into stereotypes.

You write in the Author’s Note that SNiP, which Abe is diagnosed with, is a fictional disease–but that PAN, which you are in remission from, is not. How did your own experiences with illness shape the novel?

The fear I had of dying young and anger at the team of specialists who couldn’t diagnose me for months informed the early short story and novella. About halfway through writing the novel, doctors found a long-term treatment which worked for me. I kept my and Abe’s symptoms the same, but I changed the name; writing about my proxy going through the worst of it while I was finally on the mend felt like tempting fate. To portray Abe’s desperation, fear, and various physical symptoms, I relied on my diary a lot.

SNiP encourages Abe to move back home, reconsider his relationship to Native medicine, and begin writing once again. What makes illness and disability such a powerful catalyst for change?

Everyone born knows we owe a death. Since we have no way of knowing when that debt will come due, it’s an abstraction, easy to push from our day-to-day thoughts. Illness makes death a reality. It’s rushing towards Abe, so he stops procrastinating and starts using his talents. Of course it did the same for me. I stopped dabbling in various stories and focused on this one.

One of my favorite scenes in Old School Indian is when Dominick chases poems around a field to catch them and bring them to Abe. How representative is this “chasing” of your own writing process?

To me prose is fairly workaday — just get up in the morning and push that cursor across the page until you have enough to work with, then chip away the excess as the shape of what you’re writing reveals itself (ideally with insight from other writers who can help you see clearly). I do it at 5:00 AM because my inner critic is still asleep at that time, which helps a lot, and instead of writing until inspiration runs out I leave a little gas in the tank for the next day, which helps even more.

Everyone born knows we owe a death. Since we have no way of knowing when that debt will come due, it’s an abstraction, easy to push from our day-to-day thoughts. Illness makes death a reality.

How did the process of writing the poetry for this novel differ from writing the narrative?

Poetry feels much different, the practice of being open to the world in the hope that some spark will show up. I kept all the windows open while drafting the poems. It seemed perfectly sane to do at the time because it worked, but in retrospect I think the Miami heat broke my internal thermometer and I’ve never quite managed to cool down. It doesn’t happen for me exactly as it does for Abe, but the poem about Elizabeth II did sit down next to me at an airport and present itself fully formed. After that, it tried to hide. Editing at the airport bar, I used it to replace a weaker poem, sent the draft off to my agent, and told her it included “my favorite thing I’ve ever written.” When I got her notes back, I realized the airport poem wasn’t there, and I couldn’t remember a word of it. It also wasn’t on my backup drive. I panicked until I remembered I was on the road, which is a different backup drive. When I looked on the travel drive and found it, it was there but not in the poetry folder. I wanted to capture those feelings, of an invisible guest, and of chasing the words of a shy poem down. Likewise, in the difference between a poem in your mind versus on the page, the line that sometimes all you’ll get is the struggle to capture it. An indie bookseller in Rhinebeck told me she has poems present themselves to her exactly as they do to Abe in the novel, so I think I got it right.

One of the things I most admire about this novel is how many threads about Native identity it manages to weave together–like, for example, Abe’s Native-Irish cousins, the family’s Thanksgiving traditions, and the divisiveness of religion in Abe’s family. Is there anything that you didn’t get the chance to write about that you would have liked to?

Dreams are important to Kanien’kehá:ka. I dropped out of college because of a dream. I was partying way too hard, and a dream told me to quit drinking and leave Syracuse University. A different parent might have gotten angry, but my mother understood completely. The first draft of Old School Indian had two or three pivotal dreams for Abe, but I couldn’t capture the significance on the page so they got cut early on.

It’s common advice that writers must “kill their darlings” as they edit their work. What is one thing that didn’t make it past the editing floor?

The flashback scene where a young Abe and Cheryl Curly Head kiss originally started with a star-crossed lovers story between a Mohawk woman named Mary Smoke and an Odawa man named Eppa Minocotab. They died on the shore of the Ahna’wate river, what became the bridge over the Raquette River. The story turned out to be just a means for me to get to the kiss, which was the important part I kept in. Mostly I miss it because I liked my quick descriptions of Mary Smoke as a “wide-hipped wonder” and Eppa as “tall and slim as a blade.” Plus finding an old-timey name like Eppa Minocotab and not using it stung.

Poetry feels much different, the practice of being open to the world in the hope that some spark will show up. I kept all the windows open while drafting the poems. It seemed perfectly sane to do at the time because it worked, but in retrospect I think the Miami heat broke my internal thermometer and I’ve never quite managed to cool down.

As Abe comes back into his being as a writer, he often laments time and the idea that he thought he would have more of it for his writing. How long has this novel lived inside of you, and how long have you been writing it?

I wrote the original short story in May of 2015 and the last draft in October of 2024, with a full-time job, domestic duties, the aforementioned health issues, a divorce, and four moves in between. There’s a story from 1979 about growing up as a Lost Child, the third-born into an alcoholic family, so parts have been inside me for a good long while. I found a picture of myself at that age, which helped me see why people consider this plot point tragic. Looking back I put myself there, not the child I was. After seeing that picture, I like to tell myself I’m taking that Lost Child on the book tour.

Debut novelist Aaron John Curtis is an enrolled member of the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe, which he’ll tell you is the white name for the American side of Akwesasne. Aaron has judged for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize, the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance prizes, the 2019 Kirkus Prize for Nonfiction, and the 2021 National Book Award for Nonfiction. Since 2004, Aaron has been Quartermaster at Books & Books, Miami’s largest independent bookstore. He lives in Miami.

SOURCE: https://pen.org/aaron-john-curtis-the-pen-ten/

Comments